Untitled

How Does it Feel?

I’ve long had a sort of running joke with myself that if your song has a refrain, you are not allowed to call it “Untitled.” And if your song is untitled, it is definitely not allowed to have a subtitle.

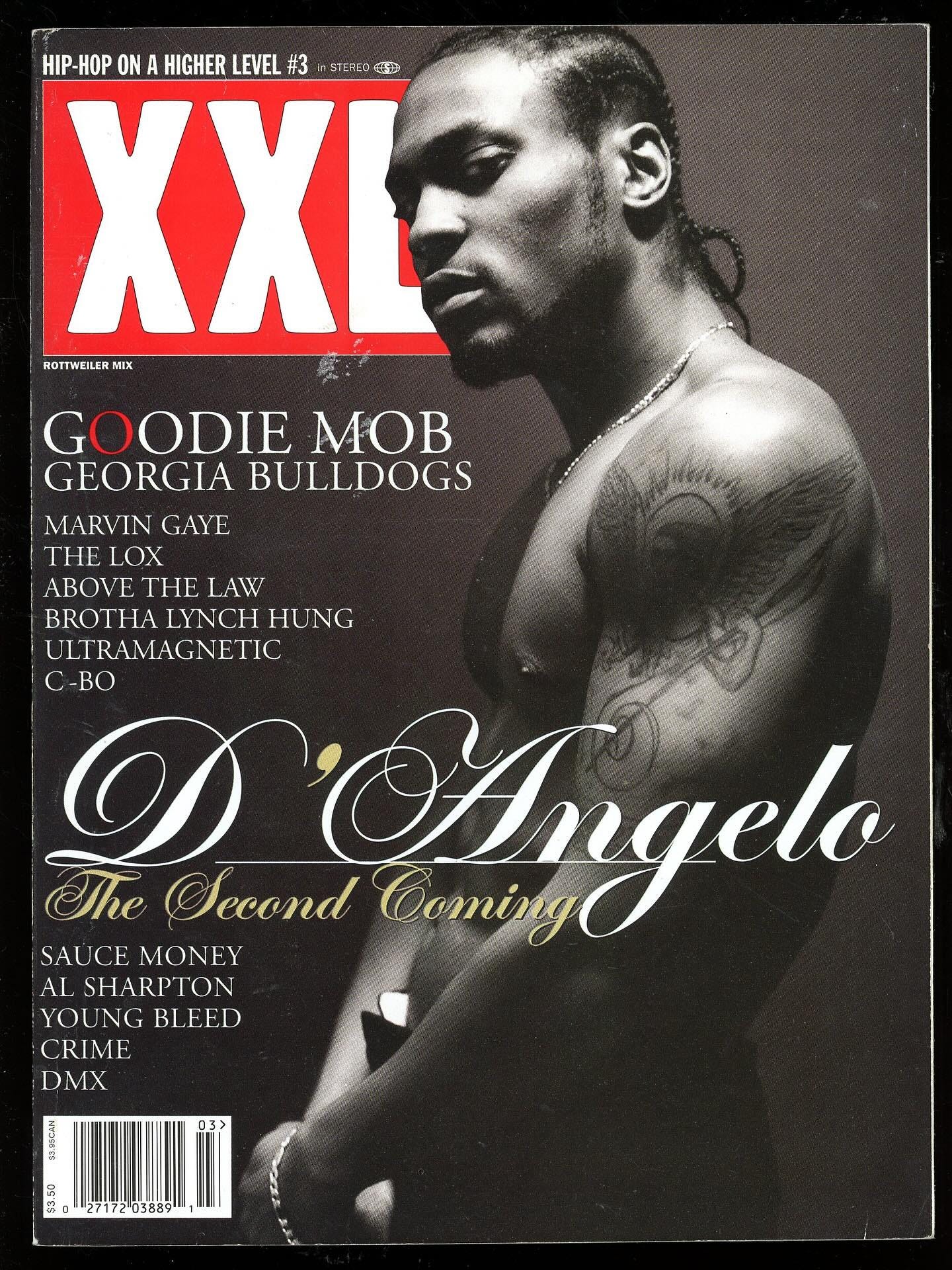

It’s a joke borne of love, of course. D’Angelo’s naming style for his hit song, “Untitled (How Does it Feel?)” is so beautifully pretentious that it always evoked a smile, and fond memories of the end of the twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty-first—a transition period for me from young adulthood to proper adulthood (or a kind of quasi-adulthood, at least). The video where D’Angelo appeared naked from the waste up—symbolizing vulnerability—had the young women around me in a headlock.

If the song was any less than excellent, we’d all have long forgotten about it. For seven minutes though, D’Angelo wails in the very key of yearning and raw longing. No one in pop music does longing better than Prince, and here D’Angelo borrows his hero’s vocal tone and musical style, not in an act of imitation, but in homage, as if to say, Here is my offering, teacher; here is what I am able to do with what you’ve taught me.

“Untitled (How Does it Feel?” reminds us of an important lesson: all art is pastiche. Every single thing written, painted, sung, rapped, etc. stands on the shoulders of things written, painted, sung, rapped before it. D’Angelo reinterprets Prince, who reinterprets Sly Stone, who reinterprets James Brown, who reinterprets Little Richard, and on and on until everyone is reinterpreting those ancestors who stood in a Southern tobacco field inventing the blues, which was in itself a reinterpretation.

From time to time in my fiction classes, someone tries to turn in a story without a title. This is hardly ever a carefully considered artistic choice like the one D’Angelo made. Instead, its a kind of apathy by the student toward the importance of naming the thing they crafted. The title is the first opportunity for the author to shape perceptions—the beginning of the spell—and it should be carefully considered. So, my other running joke inspired by D’Angelo is that if a student turns in an untitled story, it is immediately re-titled, “How Does it Feel?” Once the title was actually apropos! I hope the student kept the title.

D’Angelo’s output was sparse—perfect, but sparse—so over time the joke lost its power as awareness of the great master’s music dimmed. As a matter of fact, I had a chance to tell the joke a few weeks ago, but I determined the explanation just wasn’t worth the class time. Kinda made me sad, you know.

When I had the opportunity, though, to snatch the naming convention in my short stories, I took it. A few years back, while working on a series of stories about a tenant in a broken-down apartment complex who expresses his love for his slumlord in a series of complaint/love letters, I came upon a story in the sequence that I didn’t have a title for. This allowed me to extend the running joke by snatching the name for my story. So I’ll share it below with you.

Peace.

[UNTITLED (HOW DOES IT FEEL?)] My Dearest Slumlord, I understand sometimes why it is I do this now; I write these letters to you out of a violent and inelegant delusion that these words will put the world, at least my world, into a better order. And to keep writing, to finish one of these missives, I must forget that one day I’ll face the ultimate reckoning; I’ll be forced to come to a final understanding that these words are just words, and words can only do so much. And that my love is just love and love improperly expressed is also the most effective dagger for practicing the art of seppuku. * You know how you step on an ant, but you don’t kill it, you simply leave it traumatized, twitching and tweaking? It half-hopes to escape and recover, live another day to again seek out sugar, or grease, or crumbs, but it also half-hopes that another foot will arrive, smash down and forever take away its pain. We’re well acquainted with ants round here, aren’t we? They march the walls with unbroken impunity. Felt I’d become a drone ant beneath the rages of this apartment complex, half crushed and staggering, hoping to survive another day, or to have all my miseries swiftly removed. * One day the serpent who frequents my balcony rapidly and repeatedly jabbed his face against the screen to get my attention, and wouldn’t you know it, he popped thing loose. Of course, you know this because my wife asked me to put in a repair request and I forgot, but when I remembered, I did, and then I called but you never responded. I grew tired of contacting you, and I complained excessively about your silence, your raw apathy, and you know what my wife said to me, she said: You know, you could fix it yourself. And I replied. Yeah, I guess I could. But then I never did. One day the serpent said to me: I talk to Gail too sometimes when she comes out here. Oh yeah? I replied. She's never mentioned it. Yeah, we eat apples and laugh— —That’s very biblical— —and she complains about the screen, and the trash, and the… —You know, it was you who broke the screen, right?— —…light fixture in her room, and the loose board near the steps by the front door, and… I went back inside and slid the door closed, though I don’t think the serpent noticed. I could still hear him outside continuing his litany of needed repairs as if I stood there next to him. * Some days I wake gasping and coughing, one hand clutching my chest or my throat, the other reaching into the air, trying to grasp a breath that feels like it’ll never arrive. My wife calls this my performance. She laughs as one laughs at a clown, with bitter contempt. I think of Pimpsey, my favorite riverbeat singer who died in this way. How he made a living of masterful scatting performances, expelling air from his lungs to create meaning and emotion with sound. He used the same passageways that would one day betray him. And that’s how it feels everyday in this thousand square foot tomb. This box. Whether I am actively fighting for a breath or not, I feel like I am choking, like I am dying. I know what Pimpsey’s last moments were like—I live them nearly every time I wake—and they weren’t peaceful, or easy, or light. He died as if in a war, struggling and battling for breath. And when she mocks me, I want to join that singer in perfect stillness just to prove a point. Some people will sit by the shore and watch you drown, and then they’ll yell at you for not sitting there with them to admire the sunset. * The serpent slithered back out there the next day, curling himself around the bird feeder. I lit a joint and shook my head watching him. Has that ever worked? I asked. Is there a bird dumb enough not to notice your scaly ass lying there? If you didn’t keep blowing up my spot I’d catch me a few, the snake replied. Give me a hit of that Starr Product, chief. It’s not Starr Product, mack, it’s Sour Diesel. Okay, give me some of that Sour D, then, baby. Your pickup lines are almost as bad as your hunting techniques, I said, and held the joint toward him. You’re a Christian, same as I am, he said. So you know that God took my arms because of what my bastard ancestor did in the Garden. I put the joint to his snake mouth and the serpent pulled in a lungful, closed his eyes and blew the smoke out slowly. Aww, that’s some good stuff, he said. Some real good stuff. The snake became quiet as if contemplating the ageless wisdom of his ancestor, the defiler of the Garden. Say man, he said. Why you keep calling that tool you plunge into your shitty toilet a snake? Shit’s offensive, you know. It’s like if I started calling snake shit humans or something. Like if I was about to go take a dump and I was like, I got to go take a human. That’d be fucked up, right? Ah, man, I said come off it— Then the serpent opened his jaws wide and sunk his fangs deep into my hand. I screamed and dropped the joint to the balcony floor. Such excruciation, my blood a blackish-red as it poured from my wounds. I went mad nearly immediately. If I had a cutlass near me, that hand would be laying right there on the floor next to my smoldering blunt. Snake, I said, I just gave you a hit of my joint and some good conversation, why would you do this? You knew I was a snake when you started smoking with me. That’s just a cliché, I said incredulously. It’s true though, isn’t it? Love,